3. The Spiral Curriculum. The liberal arts, of course, are not everything. They were not the whole of ancient education either. For Plato a rounded education would begin with "gymnastics", meaning physical education and training in various kinds of skills, and "music" meaning all kinds of mental and artistic training. In the Laws (795e) he describes these as physical training for the body (including dance and wrestling or martial arts), and cultural training for the personality (including sacred music), so that young people spend practically their whole lives at "play"(sacrificing, singing, dancing: 803e) in order to win the favour of the gods.

The range of studies that were later codified as the liberal arts are to be built on this double foundation, and they in turn are for the sake of our growth in true inner freedom, in preparation for the highest studies – the contemplation of God, in philosophy and theology. In the Laws, Plato calls the liberal arts studies for "gentlemen", although he specifies that even the "man in the

street" and "tiny tots" should be taught the rudiments. In this place he divides them into three, in addition to the music and dance discussed earlier: "(1) computation and the study of numbers; (2) measurements of lines, surfaces and solids; (3) the mutual relationship of the heavenly bodies as they revolve in their courses" (817e).

An education devised along these lines (not too slavishly, because Plato's proposed legislation can be rather oppressive) could be said to be based upon a spiral curriculum, since each of the essential elements are returned to again and again, each time at a higher level of development, until the gaze of man is entirely on God, through the ascending path of a dialectic that leads beyond argumentation towards contemplation.

The liberal arts are not for the sake of anything else; they are not vocational in any narrow sense. They contain their aim within themselves. Even the study of numbers and ability to measure is not strictly for the sake of the many practical applications to which these skills lend themselves. In themselves, taught in the right way and studied in the right spirit, they are really about harmony, proportion, beauty, and therefore they lead the mind to the source of all beauty.

These notes are intended to help readers engage with the text of Beauty in the Word.

NEXT: The Mother of the Liberal Arts.

Friday, August 3, 2012

Themes of the book: 2

2. The Transcendentals. I find the triad of the Trivium (Memory, Thought, Speech, or if you prefer Grammar, Dialectic, Rhetoric) echoed in many others, from the Trinity of divine persons on down through the various levels of creation. The Trivium is therefore intimately bound up with the divine image in Man, which is a Trinitarian image. God himself is the source of Memory, Thought, and Speech (Being/Father, Logos/Son, and Breath/Spirit).

One of those triads is composed of the so-called "transcendental properties of being", meaning properties that are so "general" that they can be found in varying degrees in everything that exists. The three I mean are Goodness, Truth, and Beauty – although one might also look at the threesome of Unity, Truth, and Goodness. As I explain (Beauty in the Word, p. 157), such triads are impossible to align definitively with particular members of the Trinity, because they can be looked at under different aspects. In fact each is one of

the Names of God, and applies to all three divine persons. The human being who searches for any of them is on the road to God, on whom these three roads converge. The Transcendentals are vitally important if we are to understand the world as a cosmos and build a civilization worthy of our humanity.

I want to propose an idea that came to me after writing Beauty in the Word, that might serve as an interesting footnote, or open up another avenue to explore. It is this. Human civilization seems to have three pillars: Law, Language, and Religion. It is these that make us into a community or nation. And in each case the aim or goal is one of the Transcendentals, even if they cannot reach that goal without divine assistance. The aim of the Law is goodness, the aim of Language is Truth, and the aim of Religion is (spiritual) Beauty -– that is, holiness. Culture is the result of all three; of Law, Language, and Religion acting in concert (body, soul, and spirit, as it were).

But how does this relate to the Trivium? Law it seems to me aims to recall us to our true nature, or encourages us to rise to our highest nature. In that sense it corresponds to Memory or Grammar. (The moral or natural law, as Pope Benedict has written in his little book On Conscience, may be equated with Platonic "reminiscence", which is in Christian terms an awakening to our true nature in God's intention.) Language then corresponds to Thought, meaning the human quest for truth in all things. (For in order to understand reality we must discern the Son, the Logos of all things.) Thirdly, Religion in the sense of a tradition or path of holiness is what gives the spirit that animates the community. It is this that makes us aware of our intimate relationship to each other, able to speak "heart to heart".

This is an extension of an idea I put forward in the book, that before we reform our schools we need to understand more deeply the goal of education, which is a truer humanity and a civilization of love.

NEXT: The Spiral Curriculum.

One of those triads is composed of the so-called "transcendental properties of being", meaning properties that are so "general" that they can be found in varying degrees in everything that exists. The three I mean are Goodness, Truth, and Beauty – although one might also look at the threesome of Unity, Truth, and Goodness. As I explain (Beauty in the Word, p. 157), such triads are impossible to align definitively with particular members of the Trinity, because they can be looked at under different aspects. In fact each is one of

the Names of God, and applies to all three divine persons. The human being who searches for any of them is on the road to God, on whom these three roads converge. The Transcendentals are vitally important if we are to understand the world as a cosmos and build a civilization worthy of our humanity.

I want to propose an idea that came to me after writing Beauty in the Word, that might serve as an interesting footnote, or open up another avenue to explore. It is this. Human civilization seems to have three pillars: Law, Language, and Religion. It is these that make us into a community or nation. And in each case the aim or goal is one of the Transcendentals, even if they cannot reach that goal without divine assistance. The aim of the Law is goodness, the aim of Language is Truth, and the aim of Religion is (spiritual) Beauty -– that is, holiness. Culture is the result of all three; of Law, Language, and Religion acting in concert (body, soul, and spirit, as it were).

But how does this relate to the Trivium? Law it seems to me aims to recall us to our true nature, or encourages us to rise to our highest nature. In that sense it corresponds to Memory or Grammar. (The moral or natural law, as Pope Benedict has written in his little book On Conscience, may be equated with Platonic "reminiscence", which is in Christian terms an awakening to our true nature in God's intention.) Language then corresponds to Thought, meaning the human quest for truth in all things. (For in order to understand reality we must discern the Son, the Logos of all things.) Thirdly, Religion in the sense of a tradition or path of holiness is what gives the spirit that animates the community. It is this that makes us aware of our intimate relationship to each other, able to speak "heart to heart".

This is an extension of an idea I put forward in the book, that before we reform our schools we need to understand more deeply the goal of education, which is a truer humanity and a civilization of love.

NEXT: The Spiral Curriculum.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Themes of the book: 1

My recent book, Beauty in the Word (see right), a sequel to Beauty for Truth's Sake, covers a lot of ground, so I thought it would be helpful to readers if I produced a "study guide". In a series of occasional posts, I intend to look at some of the key themes and ideas in the book.

1. The Trivium. This is what the book is about. The word refers to three of the traditional "seven liberal arts" that were the basis of the classical and medieval school curriculum, namely Grammar, Dialectics or Logic, and Rhetoric. (The other four, the so-called "Quadrivium" of Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy, were discussed in the previous book.)

I must admit, when I was first asked to write on this topic, I wondered if it could be made interesting enough. The Trivium sounded a bit boring to me, as I'm sure it does to many people. The rules for correct speech and the dry bones of logic? Give me a break! But as soon as I entered into the subject I found unexpected vistas opening up. It is a bit like entering the Tardis.

The key for me was to discover that the three elements of the Trivium link us directly with three basic dimensions of our humanity. No wonder they are so fundamental in classical education! I tried to bring out this hidden depth by talking not about Grammar and so on but about Memory, Thought, and Speech. To become fully human we need to discover who we are (Memory), to engage in a continual search for truth (Thought), and to communicate with others (Speech). (I suppose I might equally have approached these in terms of Maurice Blondel's three categories of Being, Thought, and Action.)

In modern times the most famous writer on the Trivium, whose essay "The Lost Tools of Learning" inspired the revival of classical education, is Dorothy L. Sayers. In it she wrote:

at the Poll-Parrot or imitative stage, the "Dialectic" of each subject at the Pert stage, and finally the "Rhetoric" dimension when the children reach the more Poetic or Romantic stage of their development.

It is a brilliant approach, and one that has since revolutionized education in many small schools. As she says, "the tools of learning are the same, in any and every subject; and the person who knows how to use them will, at any age, get the mastery of a new subject in half the time and with a quarter of the effort expended by the person who has not the tools at his command." It may offer a key to reversing the decline that followed the dismantling of the liberal arts in most Western countries:

NEXT: The Transcendentals

1. The Trivium. This is what the book is about. The word refers to three of the traditional "seven liberal arts" that were the basis of the classical and medieval school curriculum, namely Grammar, Dialectics or Logic, and Rhetoric. (The other four, the so-called "Quadrivium" of Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy, were discussed in the previous book.)

I must admit, when I was first asked to write on this topic, I wondered if it could be made interesting enough. The Trivium sounded a bit boring to me, as I'm sure it does to many people. The rules for correct speech and the dry bones of logic? Give me a break! But as soon as I entered into the subject I found unexpected vistas opening up. It is a bit like entering the Tardis.

The key for me was to discover that the three elements of the Trivium link us directly with three basic dimensions of our humanity. No wonder they are so fundamental in classical education! I tried to bring out this hidden depth by talking not about Grammar and so on but about Memory, Thought, and Speech. To become fully human we need to discover who we are (Memory), to engage in a continual search for truth (Thought), and to communicate with others (Speech). (I suppose I might equally have approached these in terms of Maurice Blondel's three categories of Being, Thought, and Action.)

In modern times the most famous writer on the Trivium, whose essay "The Lost Tools of Learning" inspired the revival of classical education, is Dorothy L. Sayers. In it she wrote:

"The whole of the Trivium was... intended to teach the pupil the proper use of the tools of learning, before he began to apply them to 'subjects' at all. First, he learned a language; not just how to order a meal in a foreign language, but the structure of a language, and hence of language itself – what it was, how it was put together, and how it worked. Secondly, he learned how to use language; how to define his terms and make accurate statements; how to construct an argument and how to detect fallacies in argument. Dialectic, that is to say, embraced Logic and Disputation. Thirdly, he learned to express himself in language – how to say what he had to say elegantly and persuasively."But modern education, she went on, has put the cart before the horse. It has reduced the Trivium to the teaching of various "subjects", and neglected the tools of learning. She proposed to reinvent it. She did so bearing in mind a rough theory of child development, based partly on self-observation. (I did not give this enough attention in the book, I admit, so this is by way of reparation.) She had noticed that children go through a Poll-Parrot, a Pert, and a Poetic phase before they reach puberty. At each stage a certain approach to each subject will come easier than others. Thus she writes of the need to teach the "Grammar" of the various subjects (languages, history, geography, science, mathematics, and theology)

at the Poll-Parrot or imitative stage, the "Dialectic" of each subject at the Pert stage, and finally the "Rhetoric" dimension when the children reach the more Poetic or Romantic stage of their development.

It is a brilliant approach, and one that has since revolutionized education in many small schools. As she says, "the tools of learning are the same, in any and every subject; and the person who knows how to use them will, at any age, get the mastery of a new subject in half the time and with a quarter of the effort expended by the person who has not the tools at his command." It may offer a key to reversing the decline that followed the dismantling of the liberal arts in most Western countries:

The truth is that for the last three hundred years or so we have been living upon our educational capital. The post-Renaissance world, bewildered and excited by the profusion of new "subjects" offered to it, broke away from the old discipline (which had, indeed, become sadly dull and stereotyped in its practical application) and imagined that henceforward it could, as it were, disport itself happily in its new and extended Quadrivium without passing through the Trivium.Of course, the history of the liberal arts is actually quite complicated, more so than Sayers had time to explore in a brief essay. Quite how complicated may be seen from an outstanding doctoral dissertation by the inventor of Media Studies, the philosopher Marshall McLuhan, published in 2006, long after his death. The Classical Trivium explores the development of the three elements of the Trivium, and the way each vies for supremacy until by the Renaissance they appear to have been wound around each other inseparably, only to be unpicked and stretched to breaking point by the new learning. (I have written about this already here.)

NEXT: The Transcendentals

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Christian Platonism

Christian Platonism or Augustinianism seems to be undergoing a kind of renaissance. Here are some books I have found interesting, in no particular order, with links. David C. Schindler, Plato's Critique of Impure Reason; Douglas Hedley, Living Forms of the Imagination; William Riordan, Divine Light: The Theology of Denys the Areopagite; C.F. Kelley, Meister Eckhart on Divine Knowledge; Christian Moevs, The Metaphysics of Dante's Comedy; Robert Bolton, The Order of the Ages and Self and Spirit; Adrian Pabst, Metaphysics: The Creation of Hierarchy; John Rist, What Is Truth?; Svetla Slaveva-Griffin, Plotinus on Number; and Giovanni Reale, Toward a New Interpretation of Plato [congenial with Plotinus on Number, but see critique].

Thursday, July 26, 2012

The world on a bad day

The massacre at a cinema in Colorado where audiences were enjoying The Dark Knight Rises – the culmination of Christopher Nolan's Batman movie trilogy – seems to have provoked only a feeble discussion of gun control that is going nowhere, and very little on the showing of extreme violence in movies. The contrast with an earlier superhero film I have praised here – Marvel's Avengers – is very marked. I don't believe that the fact this massacre happened during the Dark Knight Rises rather than the latter is merely coincidental. Both deal with the battle of good and evil, but in very different ways. In fact two different kinds of imagination are

involved. In order to understand this we need to look at the relation of art to entertainment to pornography.

Art can deal with any kind of subject matter, but the way it does so matters. Great art deals with its subjects in a great manner. Commercial entertainment is both (usually) crasser in its methods and more limited in what it encompasses – essentially, subjects with mass appeal, in order to maximize profit, but with certain limits, pornography being one. But the boundary between them is hard to define, or rather hard to agree upon. The most successful entertainment is often a work of art, and of course both art and entertainment may contain elements or notes of pornography (art may even deal explicitly with pornography as a topic).

Guernica by Picasso is great art dealing with the topic of state-sponsored violence. We are meant not to like it, but be disturbed by it. The Hunger Games trilogy covers the same topic in the mode of "entertainment". But a pornographic photograph or movie depicts violence in a way designed to titillate the human organism into wanting more. In fact some neurophysiologists regard pornography as addictive, due to a release of chemicals in the brain. But there is more to this than physiology.

The human imagination mediates between the senses and the intellect, or the world and the spirit. It can therefore face in two very different directions – call them up and down. Facing "up" it is open to the light of the spirit, and reveals a world of forms shining through the images it constructs. An extreme example would be an icon or work of sacred art, which acts as a window towards the heavenly world that is more real, and more eternal, than the everyday. But any great work of art, I would argue, does this in a way. For example A Child Consecrated to Suffering by Paul Klee, which bears relatively little relation to naturalistic forms, may help to reveal a spiritual essence more effectively than a photograph or naturalistic painting, or a work by a lesser artist.

But what if the imagination faces "downwards"? In certain types of surreal art (though not all) and also in pornography, whether of violence or sex, images drawn from nature are blown out of proportion and arranged in such a way as to turn the soul away from the world of the spirit and introduce it to something baser, more corrupted, and more dangerous – also something less real than the world around us. The effects on us as consumers is rapidly apparent.

The Dark Knight series is not pornography, but its imagination is looking in several directions. It looks down into the pit of evil, it glances up to archetypes of heroism, and a lot of the time it looks around at a caricature of the world in between, in order to assure us that this is what it is really about: the world of the everyday, or rather the world on a bad day. Avengers has a different balance to it. The sense of violence and evil is less overpowering, because it is not intent on gazing into the abyss; it is less oppressive, because the movie is not trying to convince the cynics among us that it is about real life. (Compare Tom Hiddleston's Loki with Heath Ledger's acclaimed Joker, both great performances.) Avengers tries to look more in the direction of the archetypes, which inspire heroes. It does so lightly, with a generous seasoning of humour. And in so doing it lifts the spirit rather than casting it down.

involved. In order to understand this we need to look at the relation of art to entertainment to pornography.

Art can deal with any kind of subject matter, but the way it does so matters. Great art deals with its subjects in a great manner. Commercial entertainment is both (usually) crasser in its methods and more limited in what it encompasses – essentially, subjects with mass appeal, in order to maximize profit, but with certain limits, pornography being one. But the boundary between them is hard to define, or rather hard to agree upon. The most successful entertainment is often a work of art, and of course both art and entertainment may contain elements or notes of pornography (art may even deal explicitly with pornography as a topic).

Guernica by Picasso is great art dealing with the topic of state-sponsored violence. We are meant not to like it, but be disturbed by it. The Hunger Games trilogy covers the same topic in the mode of "entertainment". But a pornographic photograph or movie depicts violence in a way designed to titillate the human organism into wanting more. In fact some neurophysiologists regard pornography as addictive, due to a release of chemicals in the brain. But there is more to this than physiology.

The human imagination mediates between the senses and the intellect, or the world and the spirit. It can therefore face in two very different directions – call them up and down. Facing "up" it is open to the light of the spirit, and reveals a world of forms shining through the images it constructs. An extreme example would be an icon or work of sacred art, which acts as a window towards the heavenly world that is more real, and more eternal, than the everyday. But any great work of art, I would argue, does this in a way. For example A Child Consecrated to Suffering by Paul Klee, which bears relatively little relation to naturalistic forms, may help to reveal a spiritual essence more effectively than a photograph or naturalistic painting, or a work by a lesser artist.

But what if the imagination faces "downwards"? In certain types of surreal art (though not all) and also in pornography, whether of violence or sex, images drawn from nature are blown out of proportion and arranged in such a way as to turn the soul away from the world of the spirit and introduce it to something baser, more corrupted, and more dangerous – also something less real than the world around us. The effects on us as consumers is rapidly apparent.

The Dark Knight series is not pornography, but its imagination is looking in several directions. It looks down into the pit of evil, it glances up to archetypes of heroism, and a lot of the time it looks around at a caricature of the world in between, in order to assure us that this is what it is really about: the world of the everyday, or rather the world on a bad day. Avengers has a different balance to it. The sense of violence and evil is less overpowering, because it is not intent on gazing into the abyss; it is less oppressive, because the movie is not trying to convince the cynics among us that it is about real life. (Compare Tom Hiddleston's Loki with Heath Ledger's acclaimed Joker, both great performances.) Avengers tries to look more in the direction of the archetypes, which inspire heroes. It does so lightly, with a generous seasoning of humour. And in so doing it lifts the spirit rather than casting it down.

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Science and faith together at last

The latest issue of our twice-yearly flagship journal, Second Spring, this time guest-edited by Christopher O. Blum of Thomas More College, is devoted to the relationship between faith and science – a question whose answer defines the spirit of the age. Schools and colleges will find this issue invaluable for classroom use with intelligent pupils. It covers scientism (Michael Aeschliman), neuroscience (James LeFanu), the Galileo myth, the anthropic principle, intelligent design, physics, and much more. Order now, if you don't already subscribe.

"Nature is either the source and the measure of our knowledge, or, if it is somehow beneath us and we are somehow its measure, then nature – including human nature – is merely some kind of cosmic playdough that we manipulate at will. The dire practical implications of such a view are evident to all men and women of good will. How is it to be refuted? Not so much by argument – for this view does not repose upon argument – as by example. It is by the patient and sober, but loving and attentive study of nature, and by the careful exposition and sharing of the results of that study, that confidence will be restored in the harmonious vision of nature as an ordered cosmos through which man the wayfarer makes his way home to his Creator." (Christopher O. Blum)

"Nature is either the source and the measure of our knowledge, or, if it is somehow beneath us and we are somehow its measure, then nature – including human nature – is merely some kind of cosmic playdough that we manipulate at will. The dire practical implications of such a view are evident to all men and women of good will. How is it to be refuted? Not so much by argument – for this view does not repose upon argument – as by example. It is by the patient and sober, but loving and attentive study of nature, and by the careful exposition and sharing of the results of that study, that confidence will be restored in the harmonious vision of nature as an ordered cosmos through which man the wayfarer makes his way home to his Creator." (Christopher O. Blum)

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

RSA on Academy Schools

With over 50 percent of secondary schools in the UK having converted to academy status, it is time to radically slim down the Department for Education and devolve powers to new regional or sub regional education commissioners that sit alongside an independent regulatory body, says a Report from the RSA. Of course, it is very "managerial" and not much about the content or meaning and purpose of education, but it may be useful to someone.

Monday, July 9, 2012

Friday, June 1, 2012

The question of purpose

Our society, indeed what remains of Western civilization, seems to many people to be falling apart. The economic crisis, the moral crisis, the ecological crisis, and the political crisis combine to create a “perfect storm”. But they all stem from one fundamental error. As a society, we have abandoned a sense of cosmic and moral order for the sake of unlimited growth and progress towards an entirely man-made universe.

A similar process underlies another crisis, the fifth crisis, that of education. It has the same root as the others. Education is in crisis not merely because standards of literacy or mathematics have fallen, but because we have no coherent vision, as a society, of what education is for or what it is meant to achieve. We have assumed that, if it is not merely a cage to keep our young people off the streets, its purpose is to train workers in the great economic machine, the same machine that we hope will produce endless growth. But we cannot know what education is for, since we have no idea any longer what man is for, or what a human being actually is.

As Frank Sheed once put it: “This question of purpose is a point overlooked in most educational discussions, yet it is quite primary. How can you fit a man’s mind for living if you do not know what the purpose of man’s life is?” We need a philosophy of education based on an adequate “anthropology” or picture of man, if we are to put education back on the right track.

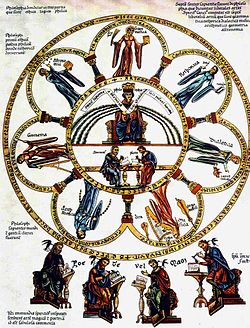

The Catholic tradition – and more broadly the great tradition of Western civilization – defined humane learning in terms of what became known as the “Liberal Arts”. As described by St Augustine and others, these consisted of seven fields of study, grouped as three arts of language, and three cosmological arts. The first group or Trivium consisted of Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric; the second, the Quadrivium, of Arithmetic, Geometry, Music and Astronomy. Both sets of arts were intended to be preparatory to the higher studies of Philosophy and Theology – that is, the love of Wisdom (philo-sophia) and the knowledge of God (theo-logos).

The Liberal Arts consituted the core curriculum at the heart of the classical and medieval educational system. I have been investigating them in two books devoted to the Quadrivium and the Trivium – Beauty for Truth’s Sake and Beauty in the Word respectively – to discover their relevance, if any, to our present educational crisis. This article is an attempt to summarize the conclusions of the two books.

There is, of course, an obvious objection to any attempt to revive this tradition today. Science has moved on since the Middle Ages. The world has changed. Why are these seven particular fields of study still of interest to us? How can we we fit other important topics like Biology, History, Geography, Sociology, Computer Studies, and the rest, into such a narrow frame? Why should we even try?

It is of course true that many things have changed. Certainly our view of the world and of ourselves has changed radically. Nevertheless, the actual world and our own nature remain what they were, and the ancient categories are still important. In the case of the Trivium, even at a superficial level it is clear that the knowledge of how languages work, how to think clearly, and how to persuade others, are all skills that are as relevant today as ever. Adding Latin and English grammar, and some training in the principles of logic and eloquence, not to mention some Great Books, to the curriculum of our modern schools would be a great idea. But the Trivium has much deeper foundations than this, as do the Liberal Arts in general.

Awakening (Trivium)

“Grammar” goes to the very root of our existence, the source of our being. In Caritas in Veritate Pope Benedict writes of the grammar of creation “which sets forth ends and criteria for its wise use, not its reckless exploitation” (48). In his Message for the World Day of Peace in 2007 he writes of a transcendent “grammar” inscribed on human consciences or on the human heart, “in which the wise plan of God is reflected”. And writing before his election as Pope he looked to Plato to help him understand this phenomenon of conscience as “something like an original memory of the good and true (the two are identical),” and therefore as an “anamnesis [reminiscence] of the Creator” (see his book On Conscience).

Grammar is not just the rules of language, but the first gift of humanity, the connection to our Origin through memory, language, and tradition. In the book I connect it with the Greek term Mythos, and the concept of telling stories to define our identity, or that of our nation and tribe. The word “grammar” was for a long time associated also with the making of magic, for with Grammar we are dealing with the deepest roots of our existence. Adam naming the animals was the first Grammarian.

With Dialectic we move from Mythos to Logos, consciously searching for the reason of things. This is the art of discerning and uncovering the truth, of distinguishing between imagination and reality. Plato’s dialogues mark the emergence of the dialectical method in its full scope, the transition from a poetic truth evoked or symbolically expressed by story and poetry into the clarity and precision of logical thought. But we need to maintain the link to the poetic consciousness – this is perhaps why Plato, even as he argued for the banishment of the artists, did so in artistic form, expressing himself through imaginative drama.

The third member of the Trivium, Rhetoric, has to do the movement from Mythos and Logos to Ethos. Far from being concerned just with the rules of eloquence, it is about the communication of souls at the level of the heart (“heart speaks to heart”), and so with the creation of community. This is more than a matter of knowing the right words. It is the art of communion, of making harmony, of bringing disparate voices into one song. The truth or Logos of the world can be communicated only in love. And until it is communicated it is not completely known.

Thus the three arts of language consisted in the reminiscence of being through Grammar, the unveiling of truth through Dialectic, and the communication of understanding through Rhetoric. With these three foundations in mind, we can begin to reconceive the curriculum of the school. The subjects we choose to teach may be very different from those studied in the Middle Ages, but that is not important. The Trivium is about the foundations on which education is built, the deeper skills that make us human, the real skills our education is supposed to bring out in us. Whatever we teach, whether it is spelling or geography, history or chemistry, we have to do it in a way that enables our humanity to grow through remembering (being), thinking (truth), and communicating (love).

Re-enchantment (Quadrivium)

Beauty for Truth’s Sake is about the Quadrivium. These four subjects are not merely “mathematical” studies in contrast to the “literary” ones. If they were, we would merely be replicating the modern divorce of science from the humanities. They are about the continued search, on the basis just established, for the Logos or Intelligibility of things.

Each member of the Quadrivium involves the study of patterns in space or time, leading to knowledge of the underlying Wisdom of the Creator expressed in the creation. This, of course, is the origin of the scientific enterprise, but it is equally the origin of art. Both are ways of discerning the Logos. Art exercises the imagination, and so in another way does science, where every major discovery has involved a creative leap. The artist searches for beauty, and so do the scientist and mathematician.

The gulf between arts and sciences, which many have remarked and debated, is not unconnected with the gulf that opened up in modern civilization between faith and reason, though they are not at all the same thing. The “reason” that can be separated from faith is a reason that is curtailed, stunted, closed to the possibility of the transcendent and so of beauty.

As I write in the book, the divorce of faith from reason led to the subordination either of faith to reason (in modernism, positivism, etc.) or of reason to faith (in the various forms of fideism and extreme biblical fundamentalism). But the seeds of the divorce lay in its reduction of reason to discursive thinking alone. Cognition has been afflicted by the same forces that afflict our freedom, and so in order to bring reason and faith together again we must understand both differently, situating them in a richer, deeper, three-dimensional world. We must understand that faith is not blind, but is a light that enables us to see even the natural world more clearly. And we must understand that reason is naturally open to God and in need of God. If we close it off to the transcendent, we do violence to its nature.

Faith is not opposed to reason, but it does function as a constant goad, a challenge, a provocation to reason. Faith claims to stand beyond reason, to speak from the place that reason seeks. But it does not claim to understand what it knows, and it should not usurp the role of reason in that sense, any more than it should contradict it.

Conclusion

The quest for the Logos is the quest for truth, beauty, and goodness. This is the search of the human heart for what it needs to flourish and be happy. And it is the only adequate basis for a philosophy of education. With its help we can construct a framework in which every type of human enquiry finds a place, losing sight neither of the way all subjects ultimately connect together, nor of the nature and needs of the human person who is the subject of education. Rather than fit the child to the Procrustean bed of economics, we fit our educational systems to the nature of the child, whose meaning and purpose transcend that of the economic machine.

Our modern curriculum is fragmented or shattered into a thousand glittering shards. The secret of their unity lies in the Logos that is the principle of unity both for the world and for the human person – for the breaking of the curriculum reflects the brokenness of the person who is the very subject of education itself.

© Stratford Caldecott, 2012

A similar process underlies another crisis, the fifth crisis, that of education. It has the same root as the others. Education is in crisis not merely because standards of literacy or mathematics have fallen, but because we have no coherent vision, as a society, of what education is for or what it is meant to achieve. We have assumed that, if it is not merely a cage to keep our young people off the streets, its purpose is to train workers in the great economic machine, the same machine that we hope will produce endless growth. But we cannot know what education is for, since we have no idea any longer what man is for, or what a human being actually is.

As Frank Sheed once put it: “This question of purpose is a point overlooked in most educational discussions, yet it is quite primary. How can you fit a man’s mind for living if you do not know what the purpose of man’s life is?” We need a philosophy of education based on an adequate “anthropology” or picture of man, if we are to put education back on the right track.

The Catholic tradition – and more broadly the great tradition of Western civilization – defined humane learning in terms of what became known as the “Liberal Arts”. As described by St Augustine and others, these consisted of seven fields of study, grouped as three arts of language, and three cosmological arts. The first group or Trivium consisted of Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric; the second, the Quadrivium, of Arithmetic, Geometry, Music and Astronomy. Both sets of arts were intended to be preparatory to the higher studies of Philosophy and Theology – that is, the love of Wisdom (philo-sophia) and the knowledge of God (theo-logos).

The Liberal Arts consituted the core curriculum at the heart of the classical and medieval educational system. I have been investigating them in two books devoted to the Quadrivium and the Trivium – Beauty for Truth’s Sake and Beauty in the Word respectively – to discover their relevance, if any, to our present educational crisis. This article is an attempt to summarize the conclusions of the two books.

There is, of course, an obvious objection to any attempt to revive this tradition today. Science has moved on since the Middle Ages. The world has changed. Why are these seven particular fields of study still of interest to us? How can we we fit other important topics like Biology, History, Geography, Sociology, Computer Studies, and the rest, into such a narrow frame? Why should we even try?

It is of course true that many things have changed. Certainly our view of the world and of ourselves has changed radically. Nevertheless, the actual world and our own nature remain what they were, and the ancient categories are still important. In the case of the Trivium, even at a superficial level it is clear that the knowledge of how languages work, how to think clearly, and how to persuade others, are all skills that are as relevant today as ever. Adding Latin and English grammar, and some training in the principles of logic and eloquence, not to mention some Great Books, to the curriculum of our modern schools would be a great idea. But the Trivium has much deeper foundations than this, as do the Liberal Arts in general.

Awakening (Trivium)

“Grammar” goes to the very root of our existence, the source of our being. In Caritas in Veritate Pope Benedict writes of the grammar of creation “which sets forth ends and criteria for its wise use, not its reckless exploitation” (48). In his Message for the World Day of Peace in 2007 he writes of a transcendent “grammar” inscribed on human consciences or on the human heart, “in which the wise plan of God is reflected”. And writing before his election as Pope he looked to Plato to help him understand this phenomenon of conscience as “something like an original memory of the good and true (the two are identical),” and therefore as an “anamnesis [reminiscence] of the Creator” (see his book On Conscience).

Grammar is not just the rules of language, but the first gift of humanity, the connection to our Origin through memory, language, and tradition. In the book I connect it with the Greek term Mythos, and the concept of telling stories to define our identity, or that of our nation and tribe. The word “grammar” was for a long time associated also with the making of magic, for with Grammar we are dealing with the deepest roots of our existence. Adam naming the animals was the first Grammarian.

With Dialectic we move from Mythos to Logos, consciously searching for the reason of things. This is the art of discerning and uncovering the truth, of distinguishing between imagination and reality. Plato’s dialogues mark the emergence of the dialectical method in its full scope, the transition from a poetic truth evoked or symbolically expressed by story and poetry into the clarity and precision of logical thought. But we need to maintain the link to the poetic consciousness – this is perhaps why Plato, even as he argued for the banishment of the artists, did so in artistic form, expressing himself through imaginative drama.

The third member of the Trivium, Rhetoric, has to do the movement from Mythos and Logos to Ethos. Far from being concerned just with the rules of eloquence, it is about the communication of souls at the level of the heart (“heart speaks to heart”), and so with the creation of community. This is more than a matter of knowing the right words. It is the art of communion, of making harmony, of bringing disparate voices into one song. The truth or Logos of the world can be communicated only in love. And until it is communicated it is not completely known.

Thus the three arts of language consisted in the reminiscence of being through Grammar, the unveiling of truth through Dialectic, and the communication of understanding through Rhetoric. With these three foundations in mind, we can begin to reconceive the curriculum of the school. The subjects we choose to teach may be very different from those studied in the Middle Ages, but that is not important. The Trivium is about the foundations on which education is built, the deeper skills that make us human, the real skills our education is supposed to bring out in us. Whatever we teach, whether it is spelling or geography, history or chemistry, we have to do it in a way that enables our humanity to grow through remembering (being), thinking (truth), and communicating (love).

Re-enchantment (Quadrivium)

Beauty for Truth’s Sake is about the Quadrivium. These four subjects are not merely “mathematical” studies in contrast to the “literary” ones. If they were, we would merely be replicating the modern divorce of science from the humanities. They are about the continued search, on the basis just established, for the Logos or Intelligibility of things.

Each member of the Quadrivium involves the study of patterns in space or time, leading to knowledge of the underlying Wisdom of the Creator expressed in the creation. This, of course, is the origin of the scientific enterprise, but it is equally the origin of art. Both are ways of discerning the Logos. Art exercises the imagination, and so in another way does science, where every major discovery has involved a creative leap. The artist searches for beauty, and so do the scientist and mathematician.

The gulf between arts and sciences, which many have remarked and debated, is not unconnected with the gulf that opened up in modern civilization between faith and reason, though they are not at all the same thing. The “reason” that can be separated from faith is a reason that is curtailed, stunted, closed to the possibility of the transcendent and so of beauty.

As I write in the book, the divorce of faith from reason led to the subordination either of faith to reason (in modernism, positivism, etc.) or of reason to faith (in the various forms of fideism and extreme biblical fundamentalism). But the seeds of the divorce lay in its reduction of reason to discursive thinking alone. Cognition has been afflicted by the same forces that afflict our freedom, and so in order to bring reason and faith together again we must understand both differently, situating them in a richer, deeper, three-dimensional world. We must understand that faith is not blind, but is a light that enables us to see even the natural world more clearly. And we must understand that reason is naturally open to God and in need of God. If we close it off to the transcendent, we do violence to its nature.

Faith is not opposed to reason, but it does function as a constant goad, a challenge, a provocation to reason. Faith claims to stand beyond reason, to speak from the place that reason seeks. But it does not claim to understand what it knows, and it should not usurp the role of reason in that sense, any more than it should contradict it.

Conclusion

The quest for the Logos is the quest for truth, beauty, and goodness. This is the search of the human heart for what it needs to flourish and be happy. And it is the only adequate basis for a philosophy of education. With its help we can construct a framework in which every type of human enquiry finds a place, losing sight neither of the way all subjects ultimately connect together, nor of the nature and needs of the human person who is the subject of education. Rather than fit the child to the Procrustean bed of economics, we fit our educational systems to the nature of the child, whose meaning and purpose transcend that of the economic machine.

Our modern curriculum is fragmented or shattered into a thousand glittering shards. The secret of their unity lies in the Logos that is the principle of unity both for the world and for the human person – for the breaking of the curriculum reflects the brokenness of the person who is the very subject of education itself.

© Stratford Caldecott, 2012

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

Dan Dare

Having written about American superhero comic books last time, I can't resist mentioning some rather different English comics many of us grew up with in the 1950s and 60s (reprinted in various forms ever since). These were immensely popular. The first issue of the weekly Eagle in 1950 sold nearly a million copies, and it ran for 991 issues. Frank Hampson's exquisitely realized drawings of spaceships and alien worlds in the Dan Dare serials no doubt inspired many a future boffin, adventurer, and artist. To find out why, explore the links. Dare was intended to be an explicitly Christian hero, in fact had originally been "Chaplain Dan Dare of the Inter-Planet Patrol", before finally appearing as the ace pilot of futuristic (and very English) Space Fleet. Eagle was founded by an Oxford-educated Anglican clergyman, Rev Marcus Morris, with its name inspired by the symbol of the Evangelist on a church lectern, and this and its sister papers Swift and Girl contained comic-book versions of the adventures of King Arthur, Robin Hood, and sundry modern missionaries, as well as sporting heroes and explorers. An education for heart, mind, and eye.

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Comic book salvation

… Stand up and keep your childishness:

Read all the pedants’ screeds and strictures;

But don’t believe in anything

That can’t be told in coloured pictures.

Chesterton would not have liked many of the stories told in coloured pictures by American comic books, which these days tend to dystopia and sado-eroticism – an all-too predictable reflection of the present state of our culture. But some he wouldhave liked, and I dare to think I could show him my own comic collection without (much) embarrassment.

My personal golden age of comics was in the late 60s and 1970s, when I would roam the streets of London looking for the latest American imports: Batman or Green Lantern, The Fantastic Four or The Mighty Thor, and a dozen other titles, illustrated by such artists as Neal Adams, the Buscema

brothers, Jack “King” Kirby, or Jim Steranko. Kirby it was who, in partnership with Stan “the Man” Lee, gave us most of the great Marvelheroes, including the Hulk, Thor, Captain America, and the Silver Surfer, and his heavily emblematic and dynamic style influenced generations of later artists. A quick scurry through Marvel-related entries in Wikipedia will explain what I am talking about, if you don’t already know. You’ll find plenty of coloured pictures, too. True, nearly all the comics I’m talking about featured punch-ups between costumed heroes and villains, and yes, there was an assortment of buxom females in tight costumes, but the appeal of the comics went deeper than that. It was the brilliance of the artistry (despite the muddy inks on cheap paper), and the way the caped crusaders tapped into archetypal, almost mythic stories, not the display of anatomy, that appealed most to me. Honestly, it was. Kirby in particular mined ancient mythology without apology to construct pantheon after pantheon of super-powered beings, ending up (at Marvel’s rival DC, publisher of Superman and Batman) with a race explicitly called the New Gods.

Superman, the progenitor of all these characters (eventually Kirby got to draw him too), was Samson and Hercules in coloured tights. After his debut in Action Comics in 1938, it didn’t take him long to become a cultural icon. If the “superman” of Nietzsche transcended conventional morality, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster’s Superman, adopted refugee from the planet Krypton and avowed defender of peace, justice, and the earth itself, accepted and upheld the moral code taught by his adopted parents in Smallville, Martha and Jonathan Kent. Right up to today, he is one of the few superheroes who remain relatively untainted by moral compromise. He doesn’t even kill; he puts villains in jail.

Superman, the progenitor of all these characters (eventually Kirby got to draw him too), was Samson and Hercules in coloured tights. After his debut in Action Comics in 1938, it didn’t take him long to become a cultural icon. If the “superman” of Nietzsche transcended conventional morality, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster’s Superman, adopted refugee from the planet Krypton and avowed defender of peace, justice, and the earth itself, accepted and upheld the moral code taught by his adopted parents in Smallville, Martha and Jonathan Kent. Right up to today, he is one of the few superheroes who remain relatively untainted by moral compromise. He doesn’t even kill; he puts villains in jail. It has taken until now for CGI to catch up with the comics. The new wave of superhero movies, especially those from the Marvel studio, boast special effects that make the earlier Superman films starring Christopher Reeve look like vintage episodes of Doctor Who, with monsters of cardboard and cellophane. One film in particular, the recent Avengers film (titled Avengers Assemble in the UK), is widely described as the superhero film that comic fans have been waiting decades to see. Anyone who sneers at it has simply never enjoyed a comic book. Up until now, superhero films have focused on one hero at a time; now the movies can do what has long delighted the fans of the comic: create teams of heroes and villains, and crossovers between one comic-book franchise and another. “The Avengers is what we call ourselves. Earth’s mightiest heroes type thing,” explains the billionaire genius philanthropist Tony Stark (a.k.a. Iron Man) to the villainous Asgardian god Loki, moments before being thrown through a skyscraper window.

The Avengers are assembled by Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson), Director of the secret agency S.H.I.E.L.D., with the aim of defending the earth against the alien army commanded by Thor’s brother. They include Captain America (Marvel’s moral equivalent to the early Superman), Iron Man (billionaire inventor in a flying suit), the Hulk (Bruce Banner, a scientist who bulks up big and green when angry), the god of thunder on assignment from Asgard, and two normal humans with heightened abilities, Hawkeye (archer with trick arrows) and Black Widow (former Russian spy and martial arts expert). The first half of the film shows our heroes squabbling, but the self-sacrificing example of a secondary (human) character, Agent Coulson, gives them the “push” they need to become a team capable of setting their egos aside and saving the world – represented, of course, mainly by Manhattan.

“There is only one God, Ma’m, and I’m pretty sure he doesn’t dress like that,” quips Captain America, in reference to the Asgardians. The line is a suitable one from the “old fashioned” Captain, who last saw action in World War Two (against a much worse villain than Hitler) and has only recently been thawed out of the polar ice where he was buried after saving the world the last time round. But, as Coulson says, “the world needs a bit of ‘old-fashioned’.”

We all need guardian angels. In fact the Catholic Church teaches that we each have one – a supernatural entity assigned at conception, not to dominate us, but to prevent us being dominated; to defend us against our supernatural enemies, giving us the space to live our human lives in a world that is much bigger and scarier than we think (what the Rangers do for the Shire in The Lord of the Rings). Comic-book superheroes and supervillains are the angels and demons of this cosmic spiritual warfare reinvented for the secular imagination, and they resonate with us because on some level we know that we need them. At the same time, they give us something to aspire to (the corresponding Christian doctrine is theosis or divinization by grace). These are not all protectors sent to us from outside – like the boy from Krypton, or Thor – more often they are ordinary human beings (Peter Parker, Bruce Wayne, Tony Stark, Hal Jordan) who by providential accident or brilliant design find themselves possessed of a power beyond the lot of mortals. And “with great power comes great responsibility”, as they quickly learn. These are flawed human beings who have to become heroes, fighting alongside the guardian angels for the right of human beings to live a meaningful life. (“I have come to set them free,” says Loki. “Free from what?” asks Fury. “Freedom,” comes the reply.)

The story that these “coloured pictures” are trying to tell us is certainly old-fashioned enough, but we never tire of hearing it. It is, as Chesterton would say, a fairy tale that holds more wisdom than most modern novels. Good and evil are real, and we define our identity and free our souls by becoming identified with the good. Heroes are not made by a burst of gamma radiation or a fancy metal suit; they are forged in a moral struggle, and the true hero is the one who is prepared to give his life to save others. And there is another way in which the coloured pictures tell the truth. Alien hordes and false gods are out there, waiting for their chance; waiting for someone to open the door to them. There is a spiritual battle going on all around us, and everyday life is part of something much bigger, something cosmic. Avengers, assemble!

Monday, May 14, 2012

Recent additions

Tow recent additions to the links column on the left: under our "Useful articles and links" see Mathematics as Poetry, and under "Fun and educational" see Learn Chemistry through comics! Thanks to readers for these tips.

Monday, May 7, 2012

Announcing a new book

BEAUTY IN THE WORD, published by Angelico Press, offers a new Catholic philosophy of education, completing the retrieval of the seven liberal arts begun in Beauty for Truth's Sake by examining the language arts, the "Trivium", which Dorothy L. Sayers made the basis of Classical Education in her famous essay, "The Lost Tools of Learning". But this book tries to go further than Sayers. Order from Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

BEAUTY IN THE WORD, published by Angelico Press, offers a new Catholic philosophy of education, completing the retrieval of the seven liberal arts begun in Beauty for Truth's Sake by examining the language arts, the "Trivium", which Dorothy L. Sayers made the basis of Classical Education in her famous essay, "The Lost Tools of Learning". But this book tries to go further than Sayers. Order from Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.New opportunities for school reform and the creation of new schools encourage radical thinking about education. We need a philosophy that can guide us as we found these new schools, or enrich and improve existing schools, or attempt to design a curriculum for teaching our children at home.

The curriculum has become fragmented and incoherent because we have lost any sense of how all knowledge fits together. What kind of education would enable a child to progress in the rational understanding of the world without losing a sense of the whole, or a sense of the sacred? We must make an effort to overcome in ourselves false ideas inculcated by the education that we ourselves received, before we can understand the elements that would make a better education possible for our children.

Anthony Esolen describes the book's purpose as laying the foundations of "an education that penetrates the heart and the mind with light." The Trivium represents the first or foundational stage of the liberal arts, understood broadly as an education for freedom. It gives us grounding for greater freedom and responsibility in three ways; that is, by developing our ability to imagine, think, and communicate. The child needs to grow in these three dimensions to be fully integrated with society. If any of the three are lacking he or she will be cut off from society and become an isolated and rather lonely particle, frenetic or depressed; one lost fragment of a broken puzzle.

+from+Wiki.jpg) In educational wisdom, the traditional "arts of language" (Grammar, Dialectics, and Rhetoric) have a key role to play.To discover this role, we need to penetrate into the deeper meaning of the "three ways" (trivium = "place where three roads meet"). As Anthony Esolen says, these reflect the three primary axes of Being: "of knowing, that is to say giving; of being known, that is to say receiving; and of the loving gift." I have referred to them under the headings of Remembering, Thinking, and Speaking, corresponding to Mythos, Logos, and Ethos. John Paul II described "the incandescent centre" of all educational activity as "co-operating in the discovery of the true image which God’s love has impressed indelibly upon every person, and which is preserved in the mystery of his own love." The whole educational process comes reaches its consummation in the liturgical act, the act of worship.

In educational wisdom, the traditional "arts of language" (Grammar, Dialectics, and Rhetoric) have a key role to play.To discover this role, we need to penetrate into the deeper meaning of the "three ways" (trivium = "place where three roads meet"). As Anthony Esolen says, these reflect the three primary axes of Being: "of knowing, that is to say giving; of being known, that is to say receiving; and of the loving gift." I have referred to them under the headings of Remembering, Thinking, and Speaking, corresponding to Mythos, Logos, and Ethos. John Paul II described "the incandescent centre" of all educational activity as "co-operating in the discovery of the true image which God’s love has impressed indelibly upon every person, and which is preserved in the mystery of his own love." The whole educational process comes reaches its consummation in the liturgical act, the act of worship.This all sounds very theoretical, no doubt – and so it is, in the original sense of theoria as "contemplation". But I have tried to show that it can be eminently practical as well, by showing how these ideas can be used to construct a curriculum. I refer in passing to the St Jerome Academy in Hyattsville, Maryland, whose "Educational Plan" (available online) has a very similar inspiration. Sequels to Beauty in the Word will include practical resources for parents and teachers, and we are looking for collaborators and advisers to join our working group in the coming months.

Here are a couple of the advance comments on the new book:

James V. Schall SJ: "Everyone recognizes the centrality of education, of introducing what is known to the one capable of knowing. What is often lacking is some sense of the whole, of some orderly way to think about the whole. It is not that we do not have a tradition that looks after the basic things and their order. It is that we have replaced what we need to know with a methodology that is based on a narrow concept of what constitutes knowing. In this insightful book, Stratford Caldecott has presented a way to understand education in a sense that includes philosophy, theology, the arts, literature, the studies of beauty and truth and what is good. It is a rare book that understands the unity of knowledge and what we want to know. This is one of those rare books."

Aidan Nichols OP: “Beauty in the Word is the fruit of a lifetime's thinking about the relation between faith and life by a cultural entrepreneur who is also a parent and knows what, educationally, can actually work. Most Catholic education has been confined not only externally, by State regulation, but also internally, owing to an inadequate philosophy of the human being in the full (and I mean full!) range of his or her capacities and needs. Now that successive governments in the UK have freed up the institutional constraints, those responsible for new initiatives in Catholic schooling have a chance to recreate the inner spirit of education and not just its outer frame. They will not easily find a programme more inspirational than the one presented here.”

ARTICLES:

The Question of Purpose

A Distributist Education

Here are a couple of the advance comments on the new book:

James V. Schall SJ: "Everyone recognizes the centrality of education, of introducing what is known to the one capable of knowing. What is often lacking is some sense of the whole, of some orderly way to think about the whole. It is not that we do not have a tradition that looks after the basic things and their order. It is that we have replaced what we need to know with a methodology that is based on a narrow concept of what constitutes knowing. In this insightful book, Stratford Caldecott has presented a way to understand education in a sense that includes philosophy, theology, the arts, literature, the studies of beauty and truth and what is good. It is a rare book that understands the unity of knowledge and what we want to know. This is one of those rare books."

Aidan Nichols OP: “Beauty in the Word is the fruit of a lifetime's thinking about the relation between faith and life by a cultural entrepreneur who is also a parent and knows what, educationally, can actually work. Most Catholic education has been confined not only externally, by State regulation, but also internally, owing to an inadequate philosophy of the human being in the full (and I mean full!) range of his or her capacities and needs. Now that successive governments in the UK have freed up the institutional constraints, those responsible for new initiatives in Catholic schooling have a chance to recreate the inner spirit of education and not just its outer frame. They will not easily find a programme more inspirational than the one presented here.”

ARTICLES:

The Question of Purpose

A Distributist Education

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Dante

Check out this superb site about the World of Dante, Italy's greatest poet. Teachers of the Comedy will find a range of materials intended to facilitate the teaching of the poem. They include a video demonstration, which introduces users to the chief components to the site and how to access them; a list of suggested activities; additional readings on the poem and on the artists whose work is included; links to other sites; and a survey. The activities work particularly well if teachers show students how to access the various materials, especially the information available on the combined text pages and search page. Or just read the poem, and enjoy the illustrations, maps, and music.

Saturday, April 21, 2012

God gives

Another very fine meditation appeared in Magnificat on 19 April 2012. By Sister Aemiliana Löhr, a German Benedictine nun who died in 1972, it expresses an important insight:

"God gives. This is the founding fact of our belief; on it revelation takes its resting-place. We know about God only because he gives himself; because he gives himself to us. God does not have something; he is everything. When he gives, he can only give himself, and thereby everything. In everything in which we receive, the gifts of nature or of grace, God gives himself; and only to the extent that we recognise that do we really come into possession of what he gives us. For all his gift can be taken from us, yet we remain in possession of his gift and favour when we see God as the heart of the gifts he gives."For more on the theology of gift see my article here, or (better yet) read the article by Antonio Lopes in the collection Being Holy in the World. Go to the Ignitum Today site for an article on Gift in relation to love and knowledge.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

Pope on beauty

The little daily prayer-book and missal, Magnificat, the International English edition of which I have the honour (with my family) of editing, contains a lot more than the texts of the Mass of the day, and prayers for morning, evening, and night. As a sample of the daily Meditations, here is an extract from the text by Pope Benedict that was published yesterday. It is about the "Way of Beauty" and the importance of art.

Incidentally, a longer and more developed discussion of Beauty by Pope Benedict (or rather Cardinal Ratzinger) is available on our main website under "Online reading", or go directly here.

"Perhaps it has happened to you at one time or another – before a sculpture, a painting, a few verses of poetry or a piece of music – to have experienced deep emotion, a sense of joy, to have perceived clearly, that is, that before you there stood not only matter – a piece of marble or bronze, a painted canvas, an ensemble of letters or a combination of sounds – but something far greater, something that 'speaks', something capable of touching the heart, of communicating a message, of elevating the soul. A work of art is the fruit of the creative capacity of the human person who stands in wonder before the visible reality, who seeks to discover the depths of its meaning and to communicate it through the language of forms, colours, and sounds. Art is capable of expressing, and of making visible, man’s need to go beyond what he sees; it reveals his thirst and his search for the infinite. Indeed, it is like a door opened to the infinite, opened to a beauty and a truth beyond the everyday. And a work of art can open the eyes of the mind and heart, urging us upward."The text has obvious echoes of Pope John Paul II's Letter to Artists, on which David Clayton's "Way of Beauty" web-site is based. David Clayton is the illustrator of several of our catechetical colouring books for children, based on traditional styles of Christian art from icons to illuminated manuscripts. In Beauty for Truth's Sake I make a case for the objectivity of beauty, in an age where many people assume it is merely in the eyes of the beholder.

Incidentally, a longer and more developed discussion of Beauty by Pope Benedict (or rather Cardinal Ratzinger) is available on our main website under "Online reading", or go directly here.

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Sex and marriage

How does a parent or teacher explain to a young person why the Church is against sex outside marriage – or rather, why the Church is in favour of sex exclusively inside marriage (and marriage between a man and a woman, to boot)? I don't know, but one important argument that is often left out concerns the nature of the human person, which is quite different from what is customarily supposed.

If human beings were simply living bodies ("ensouled bodies", because a soul is an animating form) like other animals, there would be no very strong reason against promiscuity. Evolutionary and social reasons would not suffice. Psychological factors might well be against it. Not everyone is inclined, like

swans or elephants, towards monogamy. Nor would it be easy to explain why two people who felt themselves to be deeply in love should not do what nature presses them to do, and express that love outside the sacrament.

Yet man is not just an ensouled body; he is also spirit. That is to say, there is in the human soul an interior dimension, an inner chamber, in which our particular likeness to God consists, and where our true freedom resides. This fact, which much of modern thought conspires to deny or obfuscate, transforms utterly our relationship to one another. We cannot, save by a denial of the most important part of our humanity, act towards each other as other animals do, or as our unspiritual nature on its own inclines us.

In human beings, acts tending to reproduction can and should be something free and personal, acts of love. So far, the romantic exponent of sex might find himself in agreement. But because the human being has this inner dimension which we call the spirit, a free and personal act necessarily involves this dimension very directly. A physical act of intimacy entails the "spiritual receiving-into-oneself" of the other person, not merely the receiving or giving of something physical or even psychological. And the acts concerned with generation are not merely pleasurable, but sacred. To the extent that they are deliberately willed, as expressions of a human love, they involve the giving and welcoming not just of the body, or a part of the body, but of the soul and the spirit.

The body is ever changing, its cells dying and being replaced. Our psychological states, thoughts, and feelings are also fluid. To locate the person, "myself", among these would be impossible, for the self is a totality that includes past, present, and future. My only access to that totality is through the spirit within, which transcends time, or at least is in contact with that which transcends time. The physical act of greatest intimacy, in which two bodies can potentially become one principle of generation and the source of a new life, should therefore be reserved for the union of one spiritual person with the other, a joining of two lives to create a new thing. Partial unions, that is unions not involving the spirit or transcending time, but involving merely the union of myself-as-I-happen-to be-now with some similar fragmentary state of the other, undermine the possibility of a lifelong commitment and communion of this kind, which the marriage vow is intended to express and make possible.

For more on sex and marriage, see HUMANUM.

If human beings were simply living bodies ("ensouled bodies", because a soul is an animating form) like other animals, there would be no very strong reason against promiscuity. Evolutionary and social reasons would not suffice. Psychological factors might well be against it. Not everyone is inclined, like

swans or elephants, towards monogamy. Nor would it be easy to explain why two people who felt themselves to be deeply in love should not do what nature presses them to do, and express that love outside the sacrament.

Yet man is not just an ensouled body; he is also spirit. That is to say, there is in the human soul an interior dimension, an inner chamber, in which our particular likeness to God consists, and where our true freedom resides. This fact, which much of modern thought conspires to deny or obfuscate, transforms utterly our relationship to one another. We cannot, save by a denial of the most important part of our humanity, act towards each other as other animals do, or as our unspiritual nature on its own inclines us.

In human beings, acts tending to reproduction can and should be something free and personal, acts of love. So far, the romantic exponent of sex might find himself in agreement. But because the human being has this inner dimension which we call the spirit, a free and personal act necessarily involves this dimension very directly. A physical act of intimacy entails the "spiritual receiving-into-oneself" of the other person, not merely the receiving or giving of something physical or even psychological. And the acts concerned with generation are not merely pleasurable, but sacred. To the extent that they are deliberately willed, as expressions of a human love, they involve the giving and welcoming not just of the body, or a part of the body, but of the soul and the spirit.

The body is ever changing, its cells dying and being replaced. Our psychological states, thoughts, and feelings are also fluid. To locate the person, "myself", among these would be impossible, for the self is a totality that includes past, present, and future. My only access to that totality is through the spirit within, which transcends time, or at least is in contact with that which transcends time. The physical act of greatest intimacy, in which two bodies can potentially become one principle of generation and the source of a new life, should therefore be reserved for the union of one spiritual person with the other, a joining of two lives to create a new thing. Partial unions, that is unions not involving the spirit or transcending time, but involving merely the union of myself-as-I-happen-to be-now with some similar fragmentary state of the other, undermine the possibility of a lifelong commitment and communion of this kind, which the marriage vow is intended to express and make possible.

For more on sex and marriage, see HUMANUM.

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Connected by Touch

Fairy tales are the fashionable thing in Hollywood and on TV. Every studio seems to be reinventing the classic tales – mostly with dire results. The successful new Tim Kring TV series Touch is much more original. Like the delightful film August Rush (which is based on the idea that people are mystically connected through music), Touch tells us that the world is built on numbers. The credit sequence alone is a work of art, showing a kaleidoscope of images drawn from the natural world and human society with diagrams of symbolic geometry superimposed. The story is built around a father (played by Keifer Sutherland) and his "autistic" son Jake, who won't speak or allow anyone to touch him. But the son has a gift with numbers. Naturally, in order to heighten the excitement, he is supposed to be "the next step in human evolution", and his gift enables him to predict the future, or "see" possible futures in the patterns of numbers he sees all

around him. Once the father realizes his son is trying to communicate with him entirely through numbers, he also learns that the boy is detecting examples of human suffering and potentialities for disaster, which by following the clues his son gives him he can begin to avert. He becomes an "invisible knight", doing good to people without their realizing it. Each episode is constructed around several plot threads involving characters in different continents whose stories interweave and are all resolved in the final moments of the episode. Quite often they involve mobile phones or the internet – maybe the first time these aspects of modernity have been fully integrated into a fairy tale.

Apart from its entertainment value, is there anything educational going on here? As I said in Beauty for Truth's Sake, the idea that the world is built of numbers, that numbers are in a sense "God's thoughts", goes back a long way (at least to Pythagoras) and very deep (the foundations of both art and science). The English writer John Michell once said, "The mathematical rules of the universe are visible to men in the form of beauty." It is this intuition, which I believe is valid, that Touch is trying to evoke (or the cynical might say is trying to exploit), along with the sense of providence, meaningful coincidence, and the natural moral order (though without explicit mention of God). I called it a fairy tale, and like all true fairy tales (according to Tolkien) the final resolution takes place through eucatastrophe. For all I know the series may flounder and lose its way later on, but it is off to a great start, and if it sends people off to look into the mysteries of the Golden Ratio or Fibonacci series, or just to explore the wonders of mathematics with writers like Clifford A. Pickover (see The Loom of God), or Michael S. Schneider (see his Constructing the Universe, that in itself is a good thing.

There is a further humane message in the series. It is that human beings are all connected, that we are all in relationship, and that we are meant to cooperate and work together, to help each other without seeking reward. Mathematics, beauty, and love are all connected. Even in prime time.

around him. Once the father realizes his son is trying to communicate with him entirely through numbers, he also learns that the boy is detecting examples of human suffering and potentialities for disaster, which by following the clues his son gives him he can begin to avert. He becomes an "invisible knight", doing good to people without their realizing it. Each episode is constructed around several plot threads involving characters in different continents whose stories interweave and are all resolved in the final moments of the episode. Quite often they involve mobile phones or the internet – maybe the first time these aspects of modernity have been fully integrated into a fairy tale.